It’s All Nepotism

Who Gets Hired and How: Breaking Down Two Different Systems

Isn’t Indigenous thinking full of nepotism? I’ve heard that you only get roles through your family.

This question has sat with me for a few weeks. At first, I thought it was an easy answer but every time I sat down to write it, the ideas weren’t flowing. How does one explain that relational or heredity roles are not nepotism, but western approaches are. In part because in Canada on reserve we see a lot of rampant nepotism.

First and foremost because the idea of nepotism in an Indigenous worldview makes no sense: we are all related so obviously we work with our relatives.

That said, I know that is a slippery answer – one that doesn’t wrestle with the stickiness of who is in charge and how that happens.

In almost every Indigenous community we know family names. We have a pretty good idea of where the Ribbonlegs fit compared to the Saddlebacks, or the Carrieres to the Chartrands.

It’s no different than the Hiltons compared to the Trudeaus, or Churchills compared to say, Smith or O’Malley.

So yes, nepotism and favouring relatives is rampant. On smaller reserves it is more visible because there is a smaller, more isolated population. Thus, small numbers effects make it appear more common, as does the fact it fits with our interpretation of history. Hereditary lines traced through the mother, the power is subjective a result of nepotism, but when lines are traced through the father representing an institution[i], the power is objective and merit based.

This framing supports the idea that Indigenous systems are somehow more ‘primitive’ or provably less civilized because of the subjectivity.

But that doesn’t capture the underlying ontology that creates it in the first place.

How We Understand Our Place in the World

What is the worldview that makes people reject their family as an organizing unit? Providing instead the impossible goal of needing to meet an external standard set by some vague authority to whom someone somewhere is probably accountable somehow?

Once we have a worldview, we also need a way of understanding whether what we believe is legitimate and sustainable, is it knowledge? This is our epistemology and we interpret our experience through what we know.

How do these fit together? Well, if we believe humans exist, and these humans are fundamentally flawed, we will look for evidence that supports our perspective to create knowledge. Once we identify what we consider flaws, we will develop mechanisms to enforce what we believe is “good” behaviour on others by rewarding them for behaving ‘properly’.

If, however, we believe humans are fundamentally good but malleable, we look for evidence that supports people’s ability to correct mistakes when they have the proper resources and their ability to self-govern when their communities are supportive and safe. Once we identify people who are struggling we collectively look at what might be needed to create behaviour that is self-regulated.

These are the substructures that determine whether family accountability and responsibly are a sufficient or insufficient organizing paradigm. These different philosophies need to be addressed to begin to address the difference between Western and Indigenous Systems Thinking and understand how to navigate the transition.

First, what the feck are ontology and epistemology?

At the most basic, as I understand these concepts and how I will use them as I discuss this material are:

Ontology – Worldview

What exists?

How do I know what I believe exists is what actually exists?

How do I relate to what exists?

Epistemology - Knowledge

How do I know what exists is sustainable over time?

How does what exists relate to me?

What else is there to know?

Philosophically, ontology is the way you understand existence, your place in it, and how your relationship to the rest of creation. Practically, ontology is the structural framework in which you create and hold knowledge.

Epistemology is a way of understanding whether what you know is actually what you know and if it is a true understanding of the world. Think of “There are unknown unknowns, known unknowns, known knowns, and unknown knowns” and basically this is epistemology.

Our knowledge is interpreted through our worldview, just as our ontology is impacted by our epistemology.

Shaping the Systems

At the most basic, every worldview starts with a belief about the nature of being and beings[ii].

The first crucial difference between Western thinking and Indigenous thinking about the nature of being and whether it is fixed or evolving. There is substantial literature on how the different understandings on the nature of being but for today’s purposes, these are summarised as Established Binaries and Emergent Spectrums.

Established Binaries

In the current dominant system, the majority of issues are approached from a black and white perspective: yes and no, good or bad, done or undone, fixed or broken. There is a cultural understanding that these binaries are established and fixed by a trusted authority and enforced by appropriately vetted representatives who are decision-makers for everyone.

A fundamental assumption is there is one way to behave. Safety is a function of fitting in on the correct side of pre-established, generally very narrow, definitions of success. There is only one good way.

Emergent Spectrums

Indigenous systems do not start, in general, with established binaries but rather view life as a continuous unfolding, an emergence. Multiple perspectives and interpretations provide a spectrum of possibilities for people to engage with.

The way to move forward is determined by what is known to be true through observation of all the parts of the world that will be impacted. Not just people, but land and animals, structures and traditions.

A fundamental assumption is that there are diverse ways to behave that all add to the world, and each person can choose for themselves within the boundaries of community wellbeing and cultural respect. Safety is a function of each person being sovereign in their decision about what is a good way for them.

Note the fundamental differences between Established Binaries and Emergent Spectrums and the impact how systems operate. The operating system ultimately stems from engrained assumptions about human nature and our relationship with the world around us.

These core beliefs about self and nature shape not just how we make decisions, but how we understand what it means to be human in relationship with others and our environment.

Views on Self and Nature

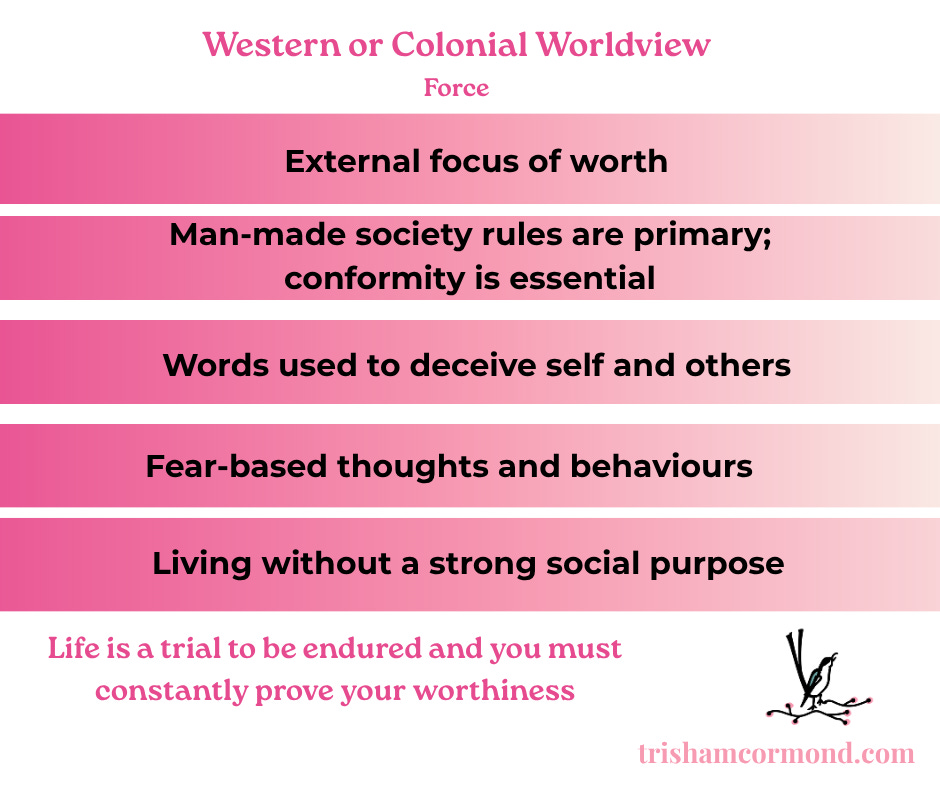

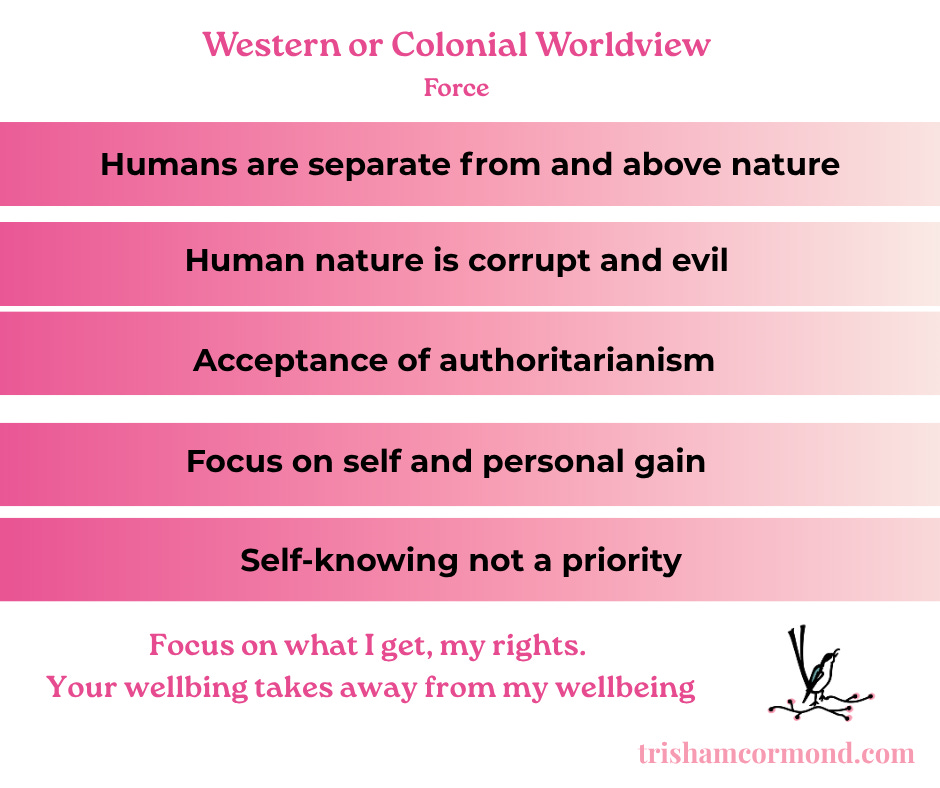

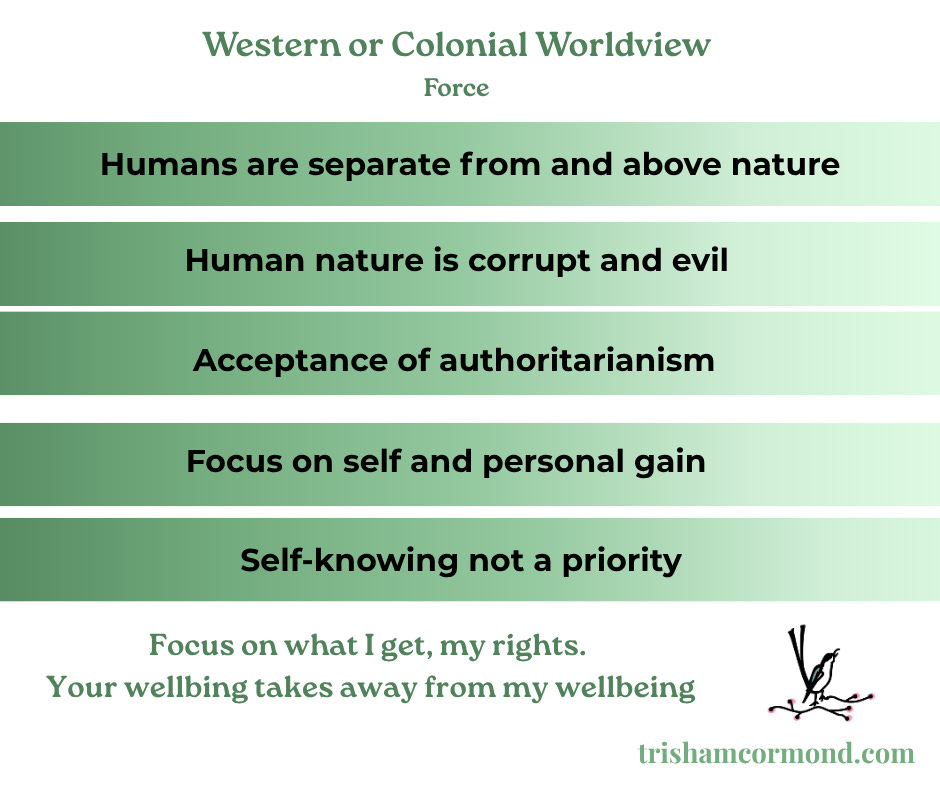

There are fundamental differences between Indigenous and Western or colonial worldview on the nature of people and the universe that shape how people interact with the world and how people make decisions.

When your worldview starts from the premise that human nature is fundamentally corrupt, you are starting at a deficit. It doesn’t matter what a person does, they can never make up for that is essentially wrong with them at the core.

Because this worldview starts by believing humans are inherently flawed, no one is deserving of support or assistance until they are already successful, and thus worthy of the resources necessary to maintain and grow that success.

In this view, belonging is not inherent but rather based on how well you perform the externally set rules.

Nature is only considered in this worldview with regard to how successful people can profit.

The belief that humans are both separate from and superior to nature, puts an incredible burden on each individual as well as on the community at large.

The aim, generally, is to make up for being less than good enough by conquering other things that are not good enough to prove that one is, at least, better than the wretched beings that you just conquered. Everyone is always in competition.

With this worldview, decisions are made to control and prevent sharing resources. That which is considered unworthy cannot benefit from that which is valuable. Various tools are used to ‘save’ resources from being wasted by people who have not proven their success.

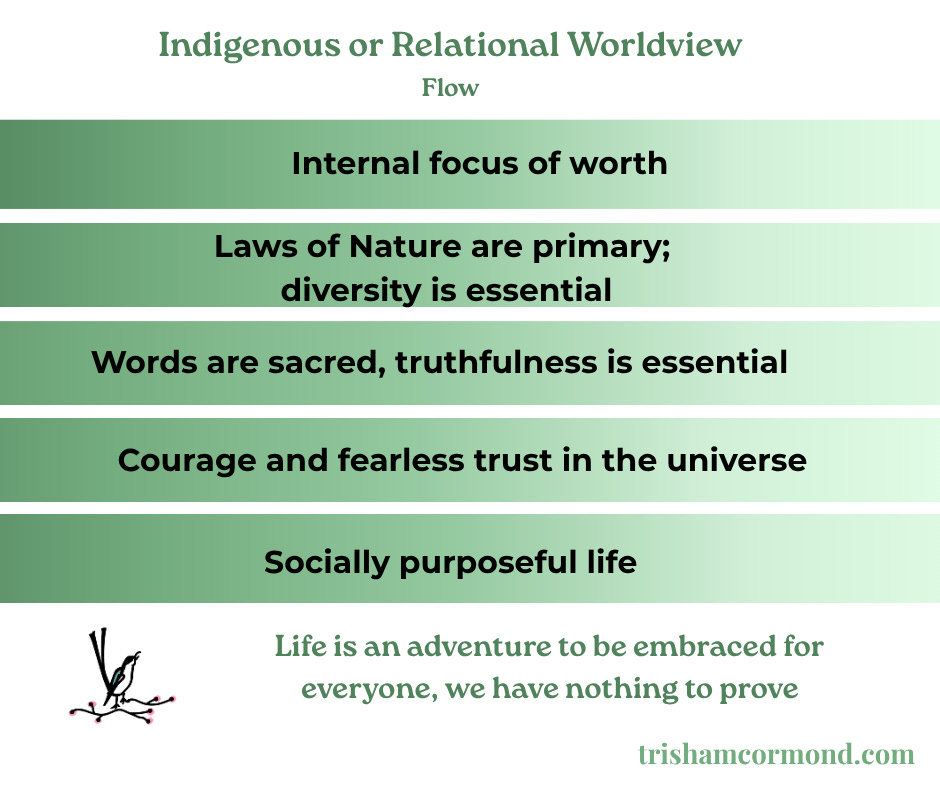

The alternative is starting from the premise that humans are part of nature, and we cannot live a good life without acknowledging and honouring this interdependence.

Wahkohtowin

This interconnected worldview is embodied in the Metis concept of wahkohtowin, which describes our nature of relationships, natural law, and mutual obligations.

We understand all aspects of life - people, land, ancestors, future generations, and all living beings – are a web of relationships carrying reciprocal responsibilities. Thus, decision-making is grounded in honouring and strengthening these relationships.

When we understand wahkohtowin, we see that what appears as ‘nepotism’ in Western systems is actually part of a sophisticated framework of multi-generational responsibilities and accountability. Family members in leadership roles aren’t simply benefiting from connections; they’re carrying forward long-standing obligations to their community, land, and future generations.

Wahkohtowin in Practice

This shift helps us to understand there is enough for everything because we all work together to create safety and wellbeing.

Actions are taken based in long-standing and thus sustainable, cultural practices that support the community. Supporting the community in turn creates safety for people to respect what others need for their wellbeing.

There is no need to take more than you need today, because it means there may not be enough for someone else. In this way, the community creates safety and trust for individuals to ask for what they need.

Since we trust in each other and the universe, there is a cultural understanding that if an individual is acting in a way that does not align with their wellbeing, the community also has a responsibility to understand why the pain?

Self-actualization grows in communities that create safety for everyone because people are able to make decisions based on what they need to feel they are living a fulfilling, responsible life.

Success is an internal experience that is supported by being part of a community that acknowledges obligation to each other[iii].

Thus, our worldviews shape our interpretation of what we experience. For example, Indigenous worldview shapes our experience of the world, it is how we understand the world and how the world understands us in relationship. This worldview understands we exist as part of something larger.

Ontology – Indigenous Worldview

What exists? I exist. All I can see and experience exists.

How do I relate to what exists? When I interact with what exists, I experience outcomes I want more or less of

How does what exists relate to me? When something interacts with me, I experience outcomes I want more or less of

In colonial worldview, there is limited understanding that we interact with the world. Disturbingly, as I was preparing the image below, I realised that for a colonial or forced worldview, understanding that the what exists relates to people is outside the acceptable boundaries because it suggests a world that is not human-centric.

Ontology – Colonial Worldview

What exists? Things have been proven by people who know more than me

How do I relate to what exists? Interaction has prescribed rules based on success of acting appropriately, as decided by a human authority

How does what exists relate to me? I do not understand the question

These fundamental differences in worldview directly impact how roles and responsibilities are assigned within communities. When humans are seen as inherently flawed, extensive, artificial validation systems become necessary to maintain an illusion of ‘separate from” the flaws of people.

In contract, when humans are seen as inherently good but malleable, community observation and relational accountability become the natural methods for understanding how everyone contributes to the wellbeing of the community as and when needed.

Hereditary Responsibilities or “Merit-based” Roles

We have arrived at the observation and question that started all this based on the concept of Relational Accountability (”Trust flows through relationship, not roles. Responsibility is shared, not assigned):

In the work I’ve done with employees (Native and non-Native) at places of tribal employment, I often hear people saying nepotism is a big problem. Perhaps you have some insight?

Short answer: Yes. Currently nepotism in First Nations is a problem. The structures put in place to meet the administrative demands of the colonial culture they must respond and report to create the conditions for nepotism.

The current model is filled with extraction and self-protection. There are a lot of places where the paid work is filled with family members of elected councillors or long-standing employees. And there are a lot of places where money is missing with nothing to show for it.

This is also true in jurisdictions governed through Western Systems Thinking.

The growth of nepotism mirrors that the practices in the colonial states that imposed these structures. Monarchy, anyone?

Nepotism is a big problem in all economies where the only goal is power, usually as measured thought money.

The Western interpretation of Indigenous hereditary roles as ‘nepotism’ fails to recognize how traditional Indigenous systems create community wellbeing through interconnected responsibilities.

Embedding leadership within a framework of relational accountability creates multi-generational obligations that extend far beyond individual benefit. Leaders are accountable not just to today’s community members, but to past teachings and future generations.

Thus, the wellbeing of the people and community they live in, coupled with long-term cultural sustainability, demonstrate whether leaders are upholding these responsibilities and contributing to the collective wellbeing of the community.

This stands in stark contrast to Western corporate nepotism, where family connections often serve to concentrate power and wealth without corresponding obligations to the broader community.

The difference lies not in whether family members hold positions of influence, but in how that influence is expected to serve and to whom people are responsible to: the greater good or individual enrichment.

Traditional Leadership Selection vs. Western “Merit-Based” Systems

Hereditary Indigenous leadership selection processes reflect a fundamentally different understanding of merit and capability. While Western systems rely heavily on credentials, competitive assessments, and individual achievements, traditional selection processes often unfold through long-term observation of character, demonstrated wisdom, and community service.

Future leaders are identified early, not through formal applications or interviews, but through their demonstrated commitment to community wellbeing and their ability to understand and honor complex relationships.

For example, potential leaders might be observed for years by elders and current leaders, who assess not just their decisions, but how they make those decisions. Do they listen to all perspectives? Do they show patience in conflict? Do they demonstrate an understanding of how their choices affect the broader community? This stands in stark contrast to Western merit-based systems that often reduce leadership potential to measurable metrics like profit generation or efficiency improvements.

There is also a competitive edge to Western systems that undermines true community because the goal is to win, not to thrive.

Why Context Matters for Interpretation

Western researchers and thus the broader public miss that nepotism is common across western economies, it’s hidden with euphemisms: “followed in her mother’s footsteps” or “His dad and uncles are all firefighters too.”

“Good at business” is a way of ignoring/erasing the broader, cultural nepotism and power dynamics that enable the accumulation of capital such that others are excluded from having their basic needs met.

Cultural artifacts also obfuscate nepotism through phrases like “Alumni clubs,” blinding us to the social networks that impact people’s access to post-secondary education. Because these external institutions have data-driven entrances standards, and networks are often invisible, there is an illusion of objectivity. This illusion obscures how people’s ability to navigate these systems is grounded in personal relationships, to name one example.

Indigenous peoples are going to act in the ways that are expected and modelled, particularly when trying to integrate the western systems thinking imposed on top of traditional governance models to meet culturally-imposed administrative demands.

When these actions are layered on top of both traditional community practices and the use of western interpretation to explain them, claims of nepotism seem to be reasonable because the argument of ‘family bias’ can be made, obscuring that Indigenous worldview that embeds long-standing obligations that are missing in Western worldview.

Anything removed from context is incomprehensible

The fact that many Indigenous Nations are/were matrilineal, and western anthropology as a discipline tends toward language like “hereditary” when speaking about different social roles as identifiers plays on and embeds the interpretation of relationships being traded for positional power.

Importantly, this western interpretation does not understand that the role is secondary to the inherent responsibilities people carry when they are in these roles. Responsibilities that are discussed and advanced based on the input from the community by youth councils, elder councils, and broader discussion.

Western Systems do not have a worldview where obligation and community wellbeing are the foundation and therefore interpretation will always be coloured by the hyper-individual competitive urgency that informs much of the systemic design.

In this way, the importance of relational structures is overlooked. In large part because there was no desire to create a theory of knowledge that was expansive enough to accept it may not be the best way to interpret the world.

From a sociological standpoint, it’s fascinating to me how quick we are to see behaviours we have been taught are irresponsible in others but blind to our own versions. Different names, comfort level, degree of familiarity are all a part of interpretation, as is how able we are to say “I don’t know.”

A Season of Reclamation is Here

To be clear, there are also a lot of Nations where nepotism is not an issue, where governance has begun to reorient toward community and responsibility once again. This return is rapid and powerful. We see it in the rising matriarchy movement and growing calls for wholisitic models of social and personal wellbeing and development.

Connecting Community Wellbeing to Leadership Effectiveness

Leadership effectiveness in Indigenous systems is inseparable from community wellbeing metrics that extend far beyond financial measures. These metrics include the community’s physical and mental health, the strength of cultural practices, the vitality of traditional languages, the health of the land and water, and the wellbeing of future generations.

When leaders make decisions that negatively impact any of these elements, their effectiveness is questioned regardless of any economic gains because there is an understanding that economic gains made at the expense of the community are not sustainable.

This holistic approach to measuring leadership success creates a natural accountability system that Western metrics, focused primarily on financial outcomes and short-term gains, often fail to capture.

Other indications include the growing number of legal actions, as well as the resurgence across cultural, economic, environmental and territorial, and food sovereignty movements.

This rising commitment to more sustainable ways of governance and decision-making is supported by emerging western science supporting how best to address macro, the growing ecological uncertainty, and micro, the number of people experiencing loneliness, challenges.

One that serves and enriches the community it is a part of rather extracting resources for an absentee landlord.

What Now?

There may be claims, as these new frameworks emerge, of nepotism and favouritism. There will probably be accusations of fraud or misuse of funds. What I mean is: There will be bumps. Some will be brutal betrayals that we need to recover from.

Betrayals exist now. These are built into the systems and we are experiencing the results in such profoundly unsettling ways right now.

The crucial difference? In the current western model, betrayals are either hidden to avoid reputational damage that may affect profits or are celebrated because they have enriched the correct stakeholder because the system prioritizes profit.

In the indigenous model, each of these betrayals provides opportunities for growth because of the commitment to accountability and truthfulness across the system because the system prioritizes relationship.

Relational Accountability in Practice

Relational accountability operates through multiple interconnected layers of responsibility and reciprocity. Leaders must regularly engage with various circles of accountability: immediate family, extended family, community elders, youth councils, and the broader community.

This practice cannot be reduced to a checklist for efficiency, because people are not efficient. Decisions are not made in isolation but through continuous dialogue and consultation.

These principles of community accountability are increasingly visible in contemporary Indigenous governance. For example, the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke has implemented a Community Decision Making Process that combines traditional consensus-building with modern governance needs. Major decisions include extensive community discussion, ensuring decisions reflect collective wisdom rather than individual authority.

Indigenous communities are reclaiming traditional accountability systems, more decisions are made with full awareness of their ripple effects across relationships and time with the intent of strengthening the web of relationships that holds people, builds community, and sustains culture over time.

Unlike Western systems where accountability often means quarterly reports and annual reviews, Indigenous relational accountability is continuous, dynamic, and embedded in daily interactions.

When a leader strays from their responsibilities, they face not just formal consequences but the immediate feedback of damaged relationships and community trust - a powerful motivator for maintaining integrity in decision-making.

Start. And Keep Going

Such a reclamation takes time and commitment, and for a long time it can look aimless – hopeless even – as a small group of people continue on guided by a common goal. Others work in isolation, driven by vision of something different and seeking others.

As this reclamation work gains momentum these smaller groups connect, more people begin to learn about alternatives to what for many years has been the status quo, and the friction starts to generate more interest.

Learning alternatives is one thing, living them is another. One of the dangers of Western Systems Thinking is how quick it is to declare failure: two missed quarters of expected results and the search for a new strategy is underway.

Thus any transition, personal or public, to a new way of relating to the world, each other, and ourselves, requires a new framework for understanding progress. An iterative approach that is grounded in community observation and connection rather than timetables.

These sorts of frameworks are less generalizable, often growing out of the community they are in and rooted in what the community needs. As frameworks are built, more and more stories will be told about strategies and weak spots to others who are working toward a sustainable, community-wellbeing model. The stories will inspire others, but not direct them.

Any questions that get us thinking about how systems operate in our communities and on our culture are important. Engaging with what we see with curiosity offers us opportunities to develop a broader worldview.

Based on this, discussion I offer the following for consideration:

1. Where do you see nepotism in your workplace or community?

2. What are the benefits and drawbacks of nepotism?

3. Is hiring your child in your business nepotism? Or is it part of building a family?

4. What kind of community do you want to live in?

5. How do your actions support the kind of community you want to live in?

[i] I know this seems like a bit of a leap, but when I say that patrilineal inheritance is institutional, what I mean is it needs something other than the woman’s word that the child is who she says it is. It is one way of removing sovereignty from women and thus, their children. It is why the Indian Act stripped status from women who married colonizers or settlers, and why women and their children continue to fight to have their ancestry acknowledged.

[ii] Please note that, as much as possible in this discussion, I am going to avoid discussions on how time is understood in these systems because it adds an unnecessary, I believe, layer of unnecessary complexity. I am also going to avoid, as much as possible, any discussions on spirituality, faith, or the divine beyond what is necessary.

[iii] I notice as I write these paragraphs, in the back of my head, there is a voice saying “well, what if Joe is fulfilled by hurting someone?” like this is some gotcha, rather than an example. My response to myself is the reminder that in a relational worldview, if Joe is fulfilled by hurting someone, it is because there is something hurting in Joe and the community will act to both protect the community while also addressing Joe’s pain with dignity. This approach reinforces relationship while maintaining dignity because human nature is essentially good, but malleable.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. Your point about 'we are all related' is so insightful. What if, on a larger scale, that intrinsic relateness could avoid clear favoritism in leadership?