Thinking about our world Shapes our World

What systems thinking means for the kind of future we are building

The other day I was asked whether, based on my expertise, Indigenous Systems Thinking, a new book from Jesse Grey Eagle, represents how Indigenous people think.

The question was “Is Indigenous Systems Thinking how all Indigenous People think? Is it fair to say that these views and ways apply to all Indigenous Peoples in North America or across the world?”

When I answered this question directly, I missed one key component - Indigenous or Western Systems Thinking is not about how each individual thinks, but rather the underlying mental models of the world in which people exist and the decisions made based upon beliefs about what the purpose of our time, and our work, here is.

Although each person’s thinking may resemble one or the other, systems thinking is more about how the community functions, how decisions are made for the collective, and the culture that results.

Systems Thinking about governance could be Indigenous in Spain just as much as they could be in Alberta, because it is about recognition of the interdependence of wakohtowin (a Michif Cree concept/word meaning all our relations, we are all related and need each other), or whatever the equivalent might be in Spain. It is a matter of reestablishing reciprocity in relationship, rather than extraction, with the people and the land the decisions impact.

So, because I suspect more people wonder the same thing when they consider Indigenous Systems Thinking, and because many people may not know what systems thinking is, this is the response I would like to give, with more thought about how the individual/community difference plays out in our experience of the world.

What is Systems Thinking?

First, we need to understand what systems thinking is, in general, without an adjective in front of it. According to a (very thorough) 2015 paper, the best definition of systems thinking is:

… a set of synergistic analytic skills used to improve the capability of identifying and understanding systems, predicting their behaviors, and devising modifications to them in order to produce desired effects. These skills work together as a system.

Which doesn’t mean a lot to me, even after having read the paper because it doesn’t tell me what it means in words that relate to the real world. (It’s linked here if you want to dive deeper into why this is a good definition, because it is - it’s just hard to understand in real life, like when you pick the store where you buy milk.)

Barry Richmond, a well-known leader in the field of systems thinking and systems dynamics, is credited with coining the term “systems thinking” in 1987. He writes (1991):

As interdependency increases, we must learn to learn in a new way. It’s not good enough simply to get smarter and smarter about our particular “piece of the rock.” We must have a common language and framework for sharing our specialized knowledge, expertise and experience with “local experts” from other parts of the web. We need a systems Esperanto. Only then will we be equipped to act responsibly. In short, interdependency demands Systems Thinking. Without it, the evolutionary trajectory that we’ve been following since we emerged from the primordial soup will become increasingly less viable.

Another definition comes from the Prevention Centre, Australia:

Systems thinking is defined as a way to make sense of a complex system that gives attention to exploring the interrelated parts, boundaries and perspectives within that system.

Rather than a systematic approach, system thinking takes a systemic approach. Research can be more effective if you use a balance of both the systematic and systemic approaches (Prevention Centre)

So (recognizing this is a simplistic breakdown) basically systems thinking examines the world and determines the way decisions are made about:

how the milk gets to the store

where that store is

who owns the store

how far it travels (also: why to a store, and not a community league)

who you are drinking the milk with

how you got the milk (barter, trade, cash)

when drinking milk is acceptable

is it cow goat or oat milk

… and why are you drinking milk anyway?

And then it considers how these different aspects interact in creating a future that is beneficial to the group for whom the decisions are being made.

Most definitions presume that the default focus for decision-making is universal, and that worldview - demonstrated through how people engage in their activities and how decisions are made at the community and governance level - is the same for everyone, or same enough that it does not need to be questioned.

But how we understand ourselves, the world and our relationship to it changes how we view and interpret systems. It’s the water we swim in, the skin we live in. It’s how our minds understand the world as interpreted through our bodies and then transmuted into a culture.

The system we live in influences what we believe about ourselves, and what we believe about ourselves helps to create (maintain) the system we live in.

Some of this worldview is definitely influenced by our education and schooling, our own curiosity and interests, our families of origin but for many of us, our worldview is rarely questioned. And that is totally reasonable - how do you know there is something to question if you don’t know there is some sort of substructure to how our minds interpret the world?

Systems Thinking is not how we think.

It is the water in which our thinking takes place.

These different ways of understanding connection (or not) shows up everyday, often in ways we don’t notice until our assumptions are challenged. Sometimes innocent questions shock us into the awareness that our worldview is not universal, even with people who appear to think the same way as us.

This sounds ridiculous - surely these are the same thing, aren’t they?

I remember a few years ago, my girlfriend and I were sitting down to dinner and she said “You know, I’ve started to wonder if maybe animals have feelings. Like, my cat snuggles with me because he loves me.”

She was silent for a moment. “What do you think?”

She had been reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass” and we’d talked about it several times, how it had influenced some of her daily decisions, so this question shocked me.

I got really still for a moment, thinking I misheard the question “I’m sorry, what? Can you repeat that?”.

“Weellll, do you think, like - do animals maybe have feelings?”

She was nervous asking this question. Her vulnerability made it clear this was not lightly asked, it had been sitting on her heart for a while. And so our dinner conversation was one I never even knew was needed.

It started with me saying “Absolutely. I absolutely believe animals have feelings, you sound nervous. Let’s talk about this.”

Reflecting later, I began to understand I did not see the world the same way other people did. It had never occurred to me that animals did not have feelings and preferences. The idea that a living creature didn’t experience the world through their body and interpret that, influencing their actions in the exact same way I do, was incomprehensible to me.

I started asking other people whether they thought animals were sentient. And more than I expected either didn’t know, or thought they weren’t.

A Quick Word on Why this Matters

Any sort of systems thinking is not about individuals and how they think about the world, although it does influence them.

Rather, systems thinking - regardless of adjective - is the worldview that is supported and maintained by the decisions that are made at the governance level, and then enacted through the daily implementation.

Going back to the definition above, systems thinking is the understanding of and lens for interpreting the world as it is experienced in the community you live in and the dominant culture it creates. Most people are completely unaware of how their daily actions either contribute to or challenge the system they live in.

This is reasonable. If we were all constantly evaluating the systems we live in, we wouldn’t be doing a lot of living.

It is, however, reasonable to reflect on whether our actions are creating the world we want, and if not - what might need to change to achieve a different outcome? Part of that is being introduced to the idea of different systems for making decisions.

Returning to the original question:

Does Indigenous Systems Thinking represent all how all Indigenous People think?

My answer: yes and no.

First, the No

Just like Western Systems Thinking both does and does not represent how all white people experience the world - there are a lot of Canadians and Americans who believe that governance should be located on and for the land and people it is making decisions about - Indigenous Systems Thinking is not how all Indigenous people experience the world - there are some who believe that profit matters more than people and it’s better to make decisions based on separation from land.

Whatever is the dominant thinking, regardless of who is making the decisions, will drive understanding of impacts and what matters in the process.

The challenge in trying to generalize anything enough for broader discussion and application is that it erases the stories and the memories that create the context for how we interpret the world. Which is what Jesse Grey Eagle is naming in his book.

Indigenous Systems Thinking is about how decisions are made for the people, land, and communities where the decisions are implemented: The collective. It takes into consideration the lived reality of the moment, is focused on the long-term wellbeing, and the sustainability of the decisions over time for the environment and the people.

The foundation is reciprocity to ensure long-term success rather than ‘how much can we take?’, there a balance between benefit and accountability asking ‘how can we work together?’

And now the Yes

The above said, IST does represent the teachings I’ve studied as Metis woman, as a mixed-culture kid raised by an Indigenous political refugee from Chile, and as an Irish woman raised among people who still follow the old ways. IST aligns with what I know through prayer, meditation, and ceremony to be a good life in a good way - miyo pimatisiwin - because it is what feels right.

The ‘yes’ is how our systems are internalized and create our own view of the world. An Indigenous worldview starts from a fundamentally different perspective on the nature of people.

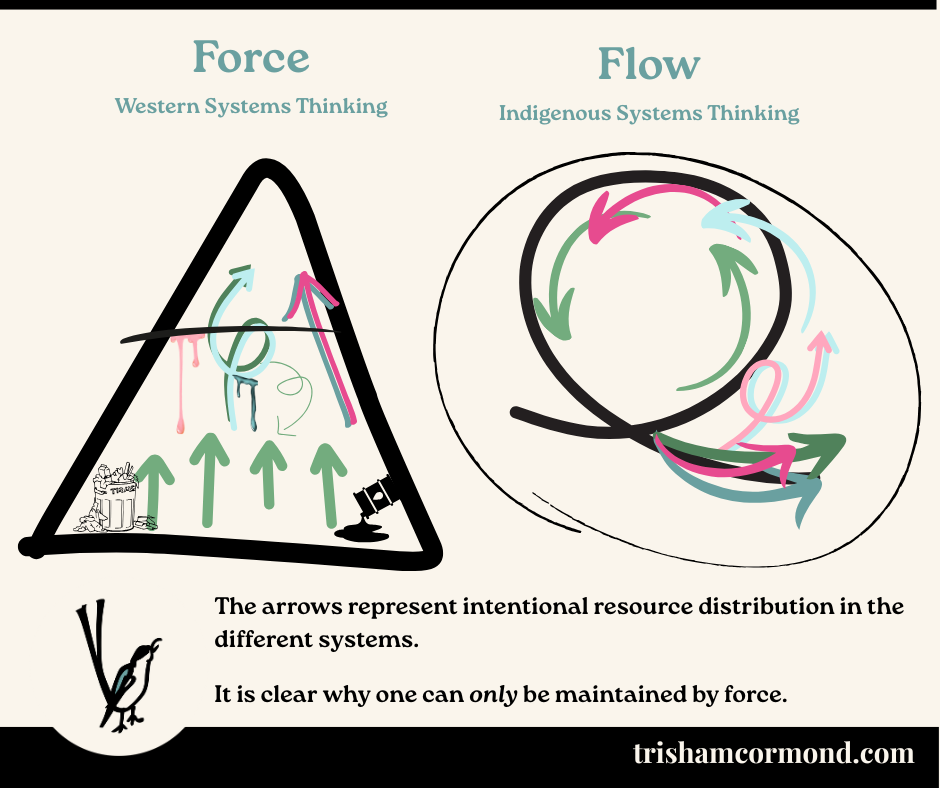

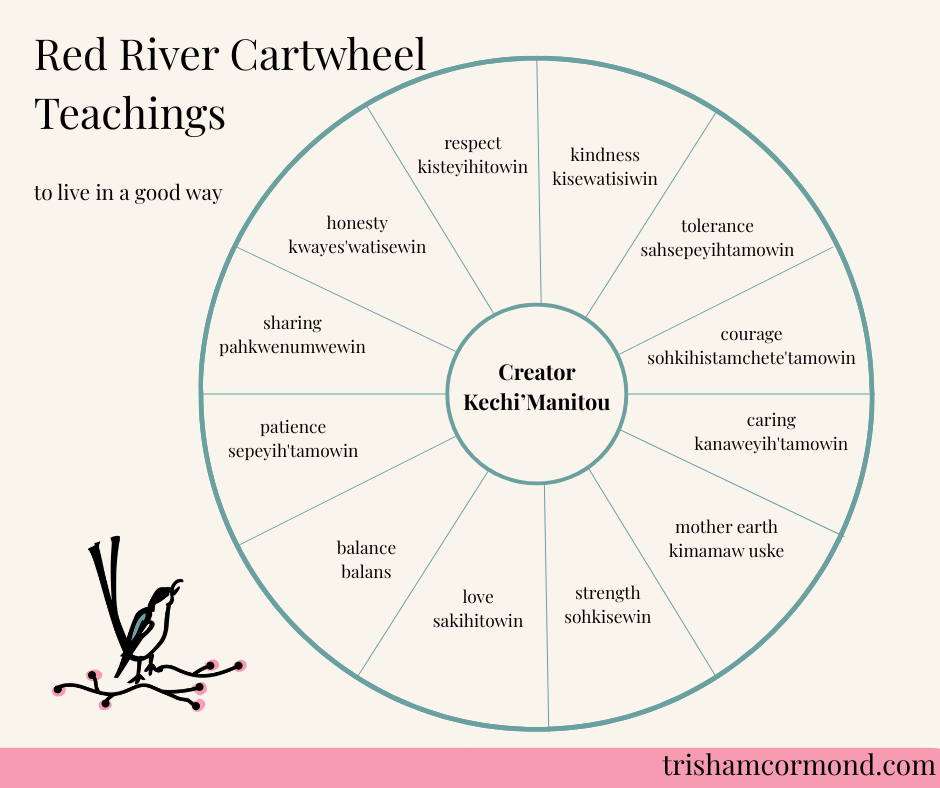

When I live this way, I don’t question if I am a good person because I have evidence. What is the evidence? Shifting from a western worldview to a Flow, or Indigenous worldview required some tools and those, for me, are the values in the Red River Cart Wheel Teachings of the Metis Nation as what makes a good life.

These values inform how I think explicitly as well as how I interpret the world. In part, I believe, because I have made a conscious decision and a consistent effort to change how I understood my relationship to the world during my personal healing. To stay well these values, from a worldview of people being fundamentally good, are how I make decisions.

So, my decisions inform the community I am a part of and how that community makes decisions. Collective (System) values guide community decisions by ensuring we take concrete action that embody these values.

Are resources stewarded?

Is community stronger?

Is there balance between all parties involved?

Can this be sustained?

These community values can only be held in place by people who have these same values and the integrity to uphold them.

Putting this into Context for Decision-Making

Thus, leadership needs a framework for decisions that ensures our values remain concrete, rather than becoming abstract principles and this framework is grounded in the land and in time. The framework has to be both internal - a commitment to personal values, and external - making public decisions that align with those values.

Shifting from a Force, or Western worldview to a Flow, or Indigenous worldview required some tools that create ways of assessing progress that goes outside of the transactional (profit-oriented) nature of Western Systems Thinking. Above I referenced the Cartwheel teachings. These are twelve values that I use for all of my decisions and that I reflect on every week.

NOTE: The Red River Cart was invented by the Metis to endure long, tough travels carrying belongings and goods for sale. It was the engine of our Nation, so it makes sense that the teachings that guide us were built into what kept us moving forward. This is another example of how culture is reinforced.

As I practiced liking myself, I used the values in the Cart Wheel teachings to assess my behaviours each week and determine whether I was acting in ways that aligned with the values I say matter to me.

Through this work the voice in my head went from shaming to loving, and how I understood work transformed. I began to understand that to do good works is why we are here, the only guarantee we have is there is work to do to care for others so that we in turn may be cared for. That for me, healing was part of that work.

This is, of course, not the only way to see the world so anyone who says they believe differently just sees the world in a way that is different from me. While I believe long-term results speak for themselves, both in my personal and my professional experience, this observation is not a judgement. We all live in the world we want to live in.

The reason I choose to see the world as an interconnected whole is because when I live in the world this way, I experience moments of true and overwhelming joy that were not available to me when I believed the delusion that I was separate from the world. At that time, I felt deeply alone and unsure of how to handle the pressure of being all-the-things to myself.

When I returned to what is, for me, correct thinking to have a good life, that anxiety and fear began to dissipate. Slowly at first as I remembered how to trust the world but the more I leaned into this worldview, the quicker my anxiety resolved into a desire to work toward something greater than where we are right now.

Why This Matters:

If the results we experience do not align with our expectations, failure and then disappointment of at least one group is the usual result. In Western Systems Thinking people often blame themselves for systemic failures. This is by design: if your worldview is that humans are evil, any failures you experience are a result of your lack.

In a system that sees aggression as courage, and you are not aggressive, this is a failure on your part and your perspective will not be considered in discussions or decisions. Similarly, if community wellbeing is less important that personal gain, decisions will reward people motivated by personal reward even if it is at the expense of community well-being.

However, the reverse is also true. If you believe people are fundamentally good, just needing guidance, then decisions are made to support community and create safe environments where everyone can flourish.

This worldview requires that nature be included because wellbeing is directly related to the health of our planet: clean air, clear water, healthy animals and plants and all other beings.

Final Thoughts

Systems thinking is about the fundamental worldview that shapes how communities and organizations make decisions which in turn shapes how people think. Whether Indigenous or Western in approach, these mental models determine how we understand our relationship with the world around us and, consequently, how we make decisions and what we expect from outcomes.

Indigenous Systems Thinking creates a framework for discussing our collective future, as well as what kind of life we want for ourselves.

Community: Leaders and decision-makers see themselves embedded in the system instead of separate from it and understand they are responsible for the impacts of their decisions. Regularly assessing how actions align with core values creates deeper integrity of action.

Harmonious Relationships: relationships are reciprocal and relational, not transactional. This shift ensures we are thinking about the impacts on the broader web of relationships and interdependencies, not just the immediate stakeholders.

Long-term Stewardship: True systems leadership means moving beyond short-term metrics to consider regenerative outcomes. This involves asking not just ‘What will this achieve?’ but ‘What kind of world will this create?’ People, their families,

and their communities benefit from the work being done, ensuring long term sustainability and abundance.

As individuals, we can only control what we do. The more of us who begin to trust the world, rather than fear it, shifting from a WST to an IST world view, means we also need to spend time

Reflecting on how our actions align with our values, and whether our actions had the intended consequences.

Developing an awareness of how everything is interconnected in our daily life helps us develop our decision-making capacity. Asking questions like ‘what community do I want to be a part of?’ is a great start.

Accepting that we can change our worldview and thus our relationship with our with thought conscious effort and regular practice.

Until I began the personal process of decolonizing my worldview and how I understand myself in the culture we live in, I did not understand how much I questioned my own perspective in a world that consistently seemed to reward bad behaviours.

We need to understand ourselves not only as impacted by the world we live in but active agents of change to create the world we want. Indigenous Systems Thinking then becomes a framework for implementation.

Eventually I understood: In our current culture most people don’t have an internalized belief system about how the world operates that supports them in their wellbeing.

In fact, it often does the opposite: Western Systems Thinking extracts from people and the environment in the maintenance of a far-away amorphous Them (empire?). It does this by providing promises that fail to appear and framing our neighbours as the problem.

The model that recenters community wellness, sustainability, and a culture of dignity for everyone is grounded in Indigenous Systems Thinking. This model supports a personal worldview of people being fundamentally good and our work is an active contributor to building the long-term wellbeing of our communities in sustainable, regenerative ways.

It is our work that builds the world we live in and determines the services we receive, I believe we should benefit from our efforts. Nature, organizations, communities, families, and people are healthier which makes our future sustainable.