The Social Breakdown We're Witnessing Isn't Random.

An Introduction to Colonial Dislocation Trauma

I heard a story once.

Two mums are catching up while watching their boys at a basketball practice.

The first mum, (Black), says “I heard Connor made the honour roll. Congratulations, you must be so proud!”

Conor’s mum, (White), says “Oh, we are. Connor’s done so well. His dad and I are delighted. And you, I heard that Jake got a full-ride scholarship. How wonderful!”

Jake’s mum says “Yes he did, thank the good Lord, because basketball’s about all that boy can do right!”

When Dr. DeGruy told that story, I was struck by how much pain we carry may have had a protective origin. On the surface, the mums react very differently. Jake’s mum sounds dismissive. Connor’s mum is obviously pleased. The two kids, hearing this, might very well think Jake’s mum is not as proud, leading to feelings of shame and confusion.

But, as Dr. De Gruy points out, when we step back and look at the legacy of enslaved families being torn apart when children were strong, obedient, and did well, Jake’s mum’s reticence to celebrate her son makes perfect sense. Even if she herself does not understand why she answers compliments with dismissal, her body and her intergenerational memory remind her: “Don’t let them know your son is a good boy,” because the outcome could be bad.

We have all sorts of syndromes or disorders named after the experiences of people in psychological pain. This may be an effective tool for helping individuals, but it does so within existing social norms. “What’s keeping you from participating in a socially acceptable way?” is the underlying question.

What might a sociological perspective reveal after decades of diagnosing symptoms for individuals with little long-term change? What if we located these various syndromes in the context of our culture?

Identifying a Systemic Wound

That kind of cultural context is exactly what sociology is designed to analyze: “the study of human relationships, the rules and norms that guide them, and the development of institutions and movements that conserve and change society.”

As a sociologist, I looked at the commonalities across these psychological manifestations and identified a unifying causal event enduring over time: a culture of dislocation from home and family as a result of colonial or capitalist endeavours.

I propose naming the social trauma created by this cultural imperative: Colonial Dislocation Trauma (CDT). By giving the source behind the symptoms a name, we provide the right target to address.

By renaming the symptoms as a result of colonial and capitalist structures and systems, two things happen:

Normal, human responses to the pain caused by bad or abusive treatment are not pathologized,

the root cause of the problem as systemic means systemic solutions can be leveraged.

Leveraging collective solutions such as appropriate mental health and wellbeing supports rather than incarceration, and making sure everyone has the basics like food and a safe place to sleep, creates broader social improvements. Every person who’s ever gone through recovery knows: first we have to accept we have a problem and then identify the problem correctly.

There are three different psychologically accepted syndromes that informed the development of CDT:

Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome

Residential School Syndrome

Boarding School Syndrome

These syndromes, born from specific historical atrocities, might seem like isolated events that impact only a segment of the population.

But they become suggestive of a wider cultural malaise when we see their symptoms mirroring the distress we are all experiencing in the general population:

Growing wealth inequality and the use of police and prisons to protect the comfort of the few.

Deteriorating working-class communities (including those who believe they are the pretend thing called the “middle class”).

Rising levels of psychiatric disorders like Borderline Personality Disorder and Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

When the general population begins to show patterns of distress that reflect the trauma of those with documented experiences of institutional abuse, a sociological explanation is no longer just a reasonable next step—it is a necessary one. (The specific connection between these modern psychiatric diagnoses and CDT will be explored in a future essay, but it is crucial to name them here as part of the wider pattern of evidence.)

1. The Beginning

Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome, named by Joy DeGruy, Ph.D in 2003, is a response in the physical, psychological, spiritual, and mental wellbeing of individuals and communities to long-term enslavement.

Multigenerational trauma together with continued oppression and absence of opportunity to access the benefits available in the society.

Joy De Gruy, Ph.D, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome

The work on Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome (PTSS) creates a lens for the trauma and pain many Black people carry. But intercontinental abduction and enslavement is not a shared experience.

Behaviour Patterns in PTSS

Vacant Self-Esteem: people experience feelings of hopelessness, depression, and engage in self-destructive behaviours

A propensity for Anger and Violence: This includes feelings of extreme distrust of others and feelings of suspicion. There are violent eruptions toward self, others, and property.

Racist Socialization/Internalized Racism: a sense of aversion for one’s self, community and culture, and heritage, with particular emphasis on physical characteristics. This, coupled with a loss of cultural and ethnic traditions and rituals undermines any sense of safety. Community cohesions, literacy and agency are negatively impacted.

2. We Never Left Our Land

For the Indigenous Peoples of North America however, the story of our dislocation happens even though we never left our lands. Rather First Nations were corralled on the land, still living and loving on them but unable to care for them the way stewardship requires. As Vine Deloria says, “on Turtle Island our God is Red.”

A lot of the focus on the Indigenous experience is Residential Schools. This resulted in Brasfield (2001) proposing Residential School Syndrome (RSS), a form of post-traumatic stress disorder. The symptomology of RSS includes:

as with post-traumatic stress disorder, the person has undergone or witnessed some degree of trauma and received insufficient care and support to recover, resulting in flashbacks, hypervigilance and dissociation.

interpersonal relationships are characterized by detachment and friction

Additionally:

loss of connection culture and language

a persistent tendency to abuse alcohol or other drugs

substance use is associated with violent outbursts of anger.

also highlights possible deficient parenting skills.

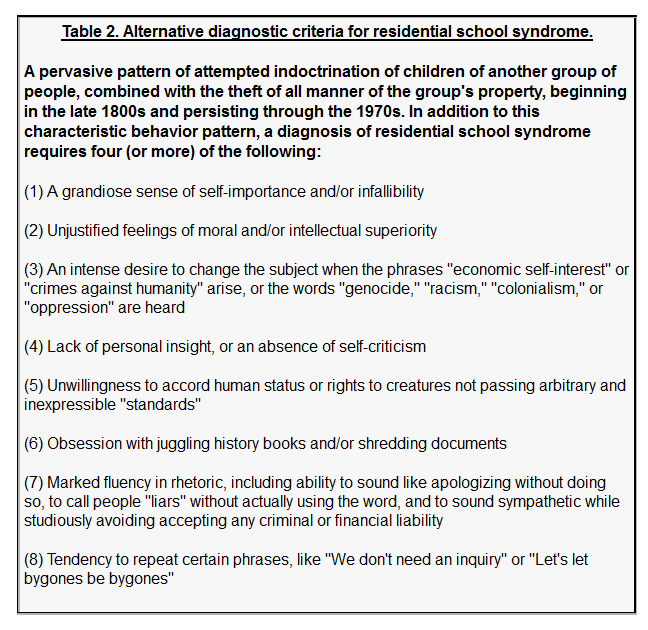

I am not the first to propose that the symptomology should focus on the perpetrators of the violence. Figure 2* shows that when Residential School Syndrome was first being proposed, many already thought it made no sense to put the weight of change on the victims rather than the people who implemented these policies.

There are attendees of residential schools who have gone on to be very successful: “I was surprised that many Saskatchewan chiefs and councillors were of the opinion that these schools had contributed to their success.” (Roberston, 2006). While uncommon, these stories of success cannot be excluded, as they are often used to defend the very system that created so much harm.

3. Colonial Success Does Not Prevent Pain

But these two separate psychological assessments do not create a pattern allowing for a broader systems theory. Until I heard about Boarding School Syndrome, something more common among those who have both the money and the desire to send their children away to school.

What was remarkable to me was the similarity of symptoms to both PTSS and RSS. Joy Schaverien is a psychotherapist who coined Boarding School Syndrome and describes the symptoms as:

Abandonment: the child has been left with strangers

Bereavement: more than just homesickness, the child is bereaved

Captivity: the child is captive in their new environment, often having to follow strict rules

Dissociation: when the child is unable to come to terms with the pain of their bereavement, they often cut off and dissociate from their feelings

People seeking mental health supports after attending boarding school report similar problems – marital difficulties, feelings of isolation, substance abuse – to those who survived other institutional systems of dislocation. Substance use, inadequate parenting skills, and mood disorders are also common.

What is notable however, is the many people who have left these boarding schools and thrived in our current capitalist culture of greed. One expert, Piers Cross, in the field notes that many of our corporate and government leaders are graduates of the same institutions he attended, and the treatment they received was no different from the treatment he received.

Syndromes and Victim-blaming

The similarities across these different Syndromes led me to question whether I was falling into the same trap at a community and cultural level that happens at the individual level when we ask women “What were you wearing?”: diagnosing the trauma but believing I’d identified the cause.

There is a Guardian headline, ‘Breaking our spirits was the plan’: the lifelong impact of having gone to boarding school’ that could have been written by any Indigenous child, or Black child but is instead a quote from an economically and socially privileged boarding school attendee.

The trauma is inherent in the system itself, poisoning the whole structure by requiring people to sacrifice their empathy to achieve success. This framework, therefore, is not just about the wounds of the oppressed; it is about creating a container for the pain in all of us caused by dislocation from our shared humanity.

Colonial Dislocation Trauma

Indigenous, or community, systems understand that our culture creates our people, and our people in turn sustain our culture, so communities must be healthy. We are both subject to and creator of the world we live in.

We are wanted in the world, and our community supports our wellbeing by ensuring everyone has food, shelter, and companionship and in turn we all contribute to our community to maintain and enrich that relationship. We are permanently located in a system and we know where we belong.

This is not the case in a colonial and capitalist system because extraction can only operate under coercive control. People understand that their ability to buy food and shelter is dependent on their ability to please their boss and keep their job, no matter how unfulfilling or undignified.

Therefore, we do not belong in a system, but rather have to constantly prove we fit in by pleasing someone with whom we have only transactional exchanges. We are dislocated from the outcomes of our work, and for many their needs outstrip what they are able to acquire because of systemic norms.

Some manifestations of Colonial Dislocation Trauma in all people affected by it:

Maladaptive Daydreaming: because of trauma, individuals create a fantasy world to escape into where they have more control. Because people are not safe to exercise their will in real life, they do so in fantasies.

Unacknowledged Grief and Shame for Grieving: There is an endless hole of loneliness when everything is ripped away and it is not acknowledged. Trauma and healing from trauma are relational. Without language for dislocation from the loss of familial relationships, and resulting grief, people can instead become angry. “Mad is sad in disguise.”

Gendered Violence: the violence perpetrated by those in power is modelled down the hierarchy, and environmental destruction has long been tied to violence against women. Resource extraction and large scale infrastructure projects, and the man-camps needed to undertake them, are closely tied to gendered violence.

Loss of connection to the real: In order to be successful in colonial states, you need to be able to ignore what your senses tell you and only believe what is written down and approved by the decision-making authorities. However this requires us to ignore what our senses tell us whenever we go outside, thus creating a split between what is known and what needs to be believed for survival in an imposed make believe hierarchy.

Perverted relationship with work: leisure as a result of hoarding and displaying wealth becomes the desired outcome of work, rather than participating in creating your life and the work of community. The impacts of business decisions on community members and the environment are ignored or covered up if businesses show profit.

Conclusion: What the Pattern Reveals

For too long, we have treated these traumas as separate tragedies. We have studied the pain of the enslaved, the Indigenous, and even the privileged elite as if they were unique, isolated events. But when we look at the mechanism—the foundational tactic—the pattern becomes undeniable.

Whether the goal was to create a compliant labour force, assimilate a “savage” population, or forge an emotionally detached administrator for an empire, the strategy was identical: break the bond between the child and their family.

This reveals a profound truth: the trauma is not a bug in our system; it is the system’s primary feature. It is a technology of disconnection designed to produce a population that is compliant, disconnected from its own heritage, and therefore easier to control.

Colonial Dislocation Trauma is the name for this feature. It is the diagnosis for the operating system itself. The manifestations we see—gendered violence, maladaptive daydreaming, perverted relationship with work, loss of connection to the real—are not our personal failings. They are the predictable, adaptive human responses to living inside a system that runs on our dislocation.

The ubiquity of these mental and social ills is not evidence of mass personal failing, but of a real and present cultural wound. Now that we have named it, we can begin to heal it.

In the next part of this series, we will examine the results of the progressive denial of pain of dislocation and how it might explain part of how we got where we are. Subscribe now to get it in your inbox

You can read part one here

References

Most are linked throughout the essay, but additional information is here:

For Figure 2: Chrisjohn R, Young S, Maraun M. The Circle Game: Shadows and Substance in the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada. Penticton, BC: Theytus Books Ltd., 1997:87.www.treaty7.org/document/circle/circle5.htm

For more on historic trauma and syndrome, Robertson, 2006 is a great discussion on whether historic trauma is actually a syndrome

Wow, Trish. This was brilliant! And also kind of terrifying. As a fellow “connector-of-the-dots”, I sometimes hate that we have this ability. Because once we see the pattern, we can’t un-see it, you know?

Was leaving a comment and Substack glitched 🤬. Anyways wanted to say I love this piece, it’s so appropriately nuanced by the commonality between symptoms of dislocation are compelling. I haven’t figured out the entirety of the insight I want to share here, but there is a familiarity I recognize in elder generations of my family who were forced to confront leaving their country of origin (Grenada, which some did and others didn’t) due to threat of US imperialism