Leaving My Job Taught Me to Love Work Again

Here's how

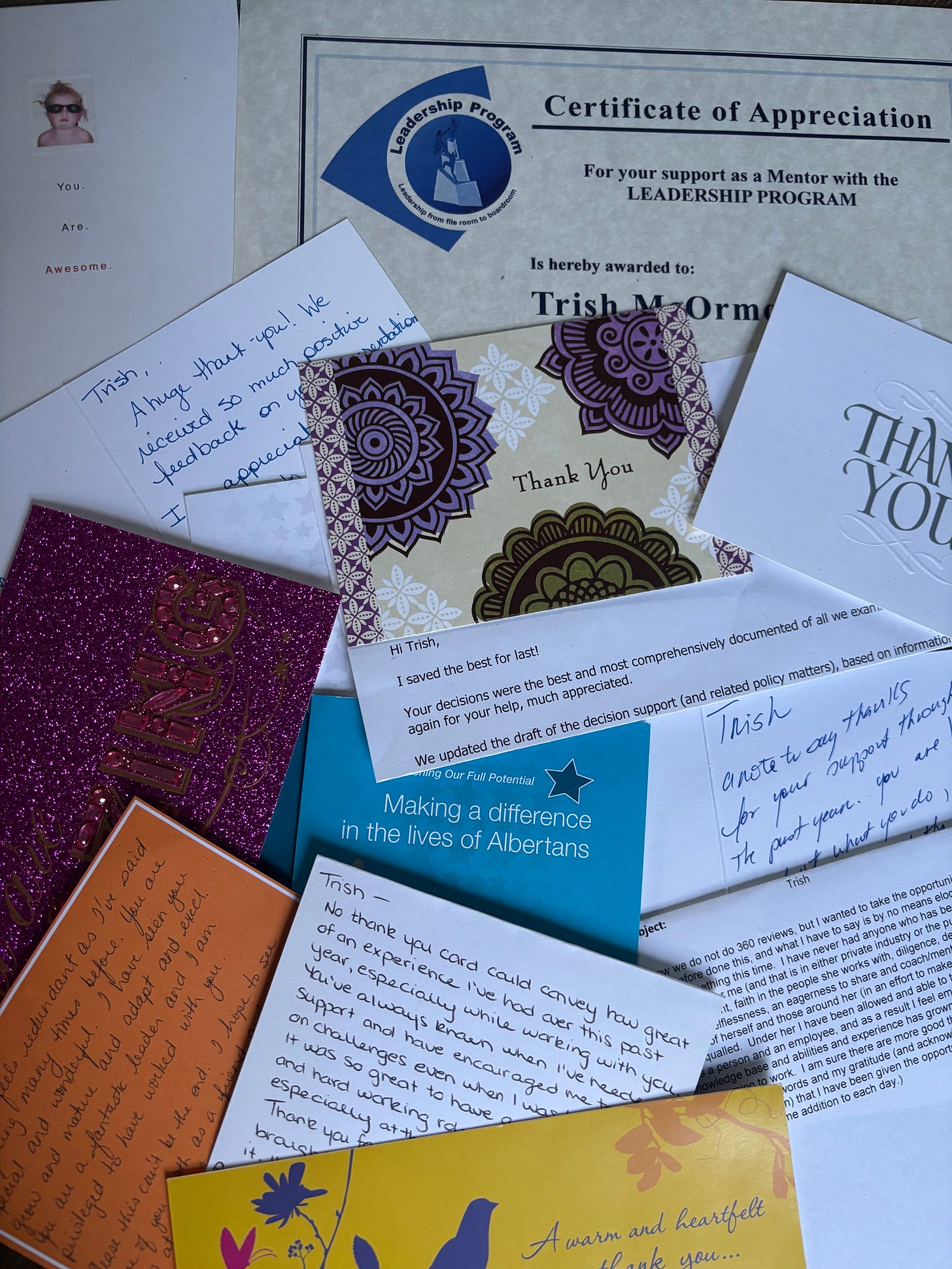

Despite the multiple thank you cards and commendations, there was a moment, as a fiercely loyal civil servant, when I realized work was poison for me.

It was later than you might expect for a labour market theorist who has spent her career thinking about meaningful work. But that’s the way with systems we’re born into—we often can’t see them clearly until we’re forced to step outside.

In part because I never really took a break to reflect on whether my values were reflected in the outcomes of the work I was doing.

Part 1: The Awakening

My journey through the civil service led to a gradual awakening, ending with a sharp kick in the teeth. At first, professional momentum coloured everything—my sense of value, my perception of impact, my belief in the importance of my work. Like many, I got caught up in wanting to please my boss and impress my colleagues. In government service, that’s not always aligned with serving the public good.

The cracks in my belief system started showing when I stayed in one senior management position long enough to see the patterns. Before that, I’d moved roles every 12-14 months, too quickly to witness the full cycle of institutional amnesia and intentional undermining that plagued our work.

What do I mean?

During a major legislative overhaul, my team made a deliberate policy decision not to build an app for assessing the affected administrative limits under new legislation. The reason? Liability.

HUGE liability.

We had received multiple legal opinions and drafted an explicit statement, agreed to by three ministers and their deputy ministers, that an app would not be considered to preserve the legislation’s integrity.

There was an unexpected twist: the government’s strategic policy coordination office partnered with a policy group to hold an innovation competition and someone submitted the idea for the very same app we had just ix-nayed.

Ironically, I had started this policy group when I joined the civil service. Though no longer an active member, I was still involved in discussions. When I saw the app listed as a finalist on the competition website, I reached out to the organizer.

I explained the legal issues and why the submission needed to be disqualified. Instead, they not only kept it in the competition—they awarded it first place for innovation. This despite our team’s proven legal concerns and the submission’s lack of any subsequent legal due diligence.

Unsurprisingly, the app never got built because legal refused to clear it. None of the other, genuinely innovative policy proposals received any attention. The competition died, and with it, a little more belief in the possibility of change died among participants.

BUT! The senior manager did get a promotion for their “commitment to policy innovation,” so all good.

This experience made it crystal clear: there was no institutional memory. Worse still, there was no desire for one. No intention to mitigate harm or build a cohesive civil service. There was only the dance of constant approval-seeking, with a made-up urgency dressed up as progress.

Part 2: The Breaking Point

Few people spoke up about their concerns and dissatisfaction in the civil service when I was a worked there because the repercussions were often dire. I experienced this firsthand in my position before leaving government. And from what I hear from former colleagues, it’s even worse now.

The breaking point came when my government employer defended misogynistic behavior and engaged in blame-the-victim games. That’s when I realized there was no organizational integrity left—no commitment to doing right by employees.

How Good People Get Caught

Let me be clear: I’m not saying there are no good people in government. The civil service is full of incredibly talented, committed individuals who go home every night struggling to understand why obvious, necessary changes are just. not. happening.

The data is clear

Solutions to social issues are widely understood

And most front-line and professional staff are deeply committed to making life better for humans. That’s why they became civil servants.

(As an aside, since leaving government I have learned that most people choose their jobs because they want to make life better for their communities and do something they enjoy. This isn’t, in my experience, always true for those leading in large consultancies, large corporations, or unfortunately, government leadership.)

But what happens is the endless recycling of the same decisions with different messaging. This devastates employee engagement, life satisfaction, and trust in the organization while concurrently undermining the population’s trust in their institutions ability to provide the right programs.

A lot of people eventually just kind of give up and start counting down the days until retirement. Legit, some people have a retirement countdown clock on their desktop. But when employers are always telling the public that the civil service needs to be cut and don’t deserve regular pay increases, why would workers give anything else?

The Executive Bubble

How does this happen?

Most bureaucrats in executive positions are captured by capital’s interests because they rarely spend time with people making under $100,000 a year (except those high-potentials marked for future leadership). Instead, they’re spending time with others in their income bracket ($250,000+) and higher. Lobbyists and consultants have endless event invitations and corporate accounts.

To be clear, this often is not intentional but rather a function of social dynamics and how power operates. In Power for All, the authors provide a case study of Vera, an NGO founder who slowly accumulated her own power, eventually alienating those she originally wanted to serve. She began to cut people off, focused on attending awards dinners rather than tending the community.

She was fortunate, she had friends, colleagues and family members who called her back into the circle. Reminding her of who she was, and she listened. Battilana and Casciaro offer this wisdom: “Having once been wary of power is no guarantee you will be immune to abusing it.”

Over time, executive civil servants’ interests align more closely with the capital class than with the population they’re meant to serve. They interpret information and make decisions with this perspective. Not because they’re bad people, but because it’s human nature to adjust your perception of “normal” based on those around you.

Even more, when an organization doesn’t believe its employees deserve good treatment, it rewards executives who share that view. And if an organization doesn’t value its own employees, it certainly has no genuine regard for the population it’s meant to serve.

“If my boss is interested, I’m captivated”

I witnessed this pattern play out in a colleague’s story—a woman who had been a vocal advocate for servant leadership and strong employee rights.

Smart and ambitious, she hit the classic ceiling: unable to make the leap from senior middle management to executive leadership. I knew the frustration well, having spent years watching less qualified people advance while I remained stuck.

I believed I could make change once I was an executive. Once I left government I realised I should have been paying attention to the current rate of change executives were achieving to understand my frustrations. So When I finally heard her introduction speech to her new team, everything became clear. I could predict:

· How she got the job

· What it cost her

· What the next 6 months would look like

My predictions proved mostly accurate. Her shift to micromanagement and “my way or the highway” thinking meant her formerly high-producing team was looking for work within a month. Within six months, most were gone, almost a quarter on medical leave.

This “didn’t bother her” because “it happened at her last job when she took over too.”

Why? Because toxic workplaces, grounded in extraction and profit-driven mentality, demand we sacrifice our integrity—our sovereignty—to be ‘successful’.

I know because I did it once too.

Part 3: The First Steps

When I first left government, fresh from what I’d call an economics-driven approach to rehabilitation, I was consumed by anger. I was convinced this had happened because no one had figured out how to address it before.

But I was obviously smarter than everyone and knew how to fix it (spoiler: I’m not smarter than everyone else, thinking that is like the number one clue I still had some learning to do).

I was going to prove to everyone that I was right and my employer was wrong.

Beyond Right and Wrong

Except… then what? What was going to get better by proving someone else wrong? Wasn’t I just doing the same thing they were and refusing to be accountable for making things better?

Through reading and research, I (re)discovered that obviously other people had had answers in the past, there was policy already in place to address the exact situation that had happened to me - and thus countless other people before me. It wasn’t lack of policy and legislation in place, it was lack of will.

Here’s a curious phenomenon about human nature: knowing something intellectually and knowing it as lived experience are completely different things. If you’re reading this thinking, “Gosh, how did Trisha not know this?”

I’d said that exact same thing about others… until it happened to me.

My initial response was predictable: anger, self-righteousness, and a burning desire to prove everyone wrong. But that’s just another form of the same poison—focusing on winning rather than healing.

The Safety Equation

So what now? Proving people wrong when an organization is designed to protect them is self-destructive. I was stuck in assigning blame and playing by the rules of the very organization that had harmed me.

Why would I want to keep engaging with the group that hurt me? I’d been doing that for decades, ending up in the same place again and again. (I’d been bullied at more than one job—it’s fairly common, check out the research from the Workplace Bullying Institute.)

Looking back now, I can see how that self-righteous anger fueled me through the fear of doing something most people don’t do: leaving a permanent government job and pulling their pension when they’re a single mom with two kids and a complex post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis.

I did it because I slowly came to understand that I didn’t feel safe returning to that employer. Everyone’s attitude seemed hostile: “What’s the big deal?”

That’s when it hit me—if my employer couldn’t care for its employees, how could it effectively and respectfully administer programs and services for the population it was supposed to serve?

The Real Data

Recent data from Gallup’s State of the Workforce (2025) report shows I wasn’t alone. Employee engagement has fallen to barely more than one in five (21 percent), with middle management engagement dropping from 30 percent to 27 percent.

Since managers are among the most influential factors for non-supervisory employees, Gallup warns that if manager engagement continues to decline, it won’t stop there—the productivity of the world’s workplace is at risk.

This research isn’t new. Wellbeing has always been linked to having meaningful work. Understanding how our labour market currently functions to make us ill sent me on a path to discover what makes us well.

Part 4: The Medicine of Meaningful Work

This journey led me beyond trauma-informed approaches to what I now call dignity-centered work—where the focus isn’t just on avoiding harm but on creating spaces where people can thrive.

Beyond Scarcity Thinking

When I started coaching people, I was still operating from a scarcity mindset—how to get more money, work harder, push more into each day. I believed success meant constant striving, that my value was tied to productivity.

Despite investing tens of thousands in coaches and programs, something still felt off. It wasn’t imposter syndrome or low self-esteem exactly. The usual suspects—fear of failure, anxiety, public speaking fears—didn’t quite fit.

I kept showing up, doing the work, trying to understand what was keeping me stuck. I had two mantras I used almost hourly:

“I am worth the work” ~ Me

“Everyone here thinks he or she is special but to be truly

special you have to know you are nothing.” ~ Mother Meera

Patterns of Healing

The breakthrough came during an inner child meditation on First Nations land. A part of me emerged that had been waiting for the right moment—not from vulnerability, but from strength and self-preservation.

She had stayed hidden until I was ready to create the safety she needed. This wasn’t just about healing old wounds; it was about reclaiming work as a way of expressing the gifts given to me by Creator rather than as mere survival in a toxic system.

I saw this pattern everywhere once I knew what to look for. I saw it in my stepdad, a political refugee, and his friends—how meaningful work helped them reclaim their place in a new community.

Those who found purposeful employment healed faster than those who didn’t. I witnessed it among my unhoused neighbours: those who found ways to contribute—picking up trash, shoveling walks—tended to fare better than those who remained isolated.

Understanding the Pattern

The research backs this up. Drake and Wallach found that “unlike most mental health treatments, employment engenders self-reliance and leads to other valued outcomes, including self-confidence, the respect of others, personal income and community integration.” It’s not just about having a job—it’s about having meaningful work that connects us to something larger than ourselves.

My growing appreciation for Indigenous ways of knowing revealed a fundamental truth: work isn’t meant to be just about monetary exchange. All Indigenous thinking, and indeed most spiritual traditions from the Bible to the Bhagavad Gita, recognize that we need each other and that work is how we support and build our communities.

This understanding cracked me open to see how monetizing labour had hidden work’s deeper meaning. Western capitalism sold us the lie of leisure while stealing our most precious resource—not the profits from our labour, but its meaning and connection to community.

When I was assaulted at work in 2019, I knew staying on disability until retirement would trap me in a different kind of prison.

True healing required reclaiming work’s transformative power. My work has given me more than purpose—it’s provided drive, focus, and ways to create new relationships across many communities.

Part 5: The Path Forward

This is what I mean by “Work as Medicine”—not just employment, but meaningful contribution that helps both the individual and community heal. When we approach work from this perspective, we move beyond trauma-informed practices to dignity-centered work, where we create spaces for people to thrive.

This stands in stark contrast to conventional wisdom, like Gallup’s suggestion that executive leaders need to ensure “middle managers are in lock-step with the executive vision”—an approach that hearkens back to early 20th century Taylorism practices requiring command and control leadership.

New Metrics for Success

Such approaches won’t work for people who want their work to have meaning. People are increasingly understanding the connection between extraction and sustainability, and they’re voting for sustainability with increasing speed. This requires a new kind of leadership and a new vision of work.

Writing this feels bizarre sometimes, 28-year-old me would totally roll her eyes and then go have a beer—because I used to have a real ‘suck it up’ mentality. The me I carry now would have been too much for that younger version. I was still in too much pain then to create something bigger than myself.

That cynicism and focus on what I could get brought me to Ottawa, then England, and eventually here. I travelled all over the world believing the job or the paycheque would change me.

Until I arrived here, in true sovereignty about how I spend my time and who benefits from my work, after a lot of growing up and a deep desire to live a life free of self-loathing.

The Transformation Blueprint

My kids were and continue to be part of that journey—how do you create a house of love if the money comes from doing things you hate?

Finally, I saw it in myself when I could hold both my most vulnerable and strongest parts without shame or anger—only gratitude for the freedom this understanding brought. When I understood that saying “I went through it and I’m fine” was the number one indicator that I was not fine.

The transformation of work from poison to medicine isn’t just about individual healing—it’s about collective liberation. When we are free, it becomes our responsibility to help free others. This is the true medicine of meaningful work.

We can start where we are, and when enough of us begin this journey, workplaces will transform themselves. Because money isn’t power—it’s control.

And when we find ways to support each other in having more control over the things that work is buying from us, when we stop allowing basic needs to be weaponized against us, money becomes less relevant.

Collective Liberation Through Work

The path forward isn’t about destroying current systems—it’s about transforming them through conscious, intentional action.

It’s about creating workplaces where dignity isn’t just a buzzword but a foundational principle. Where success is measured not just in profits but in the wellbeing of our communities.

Because ultimately, work isn’t just what we do, it’s how we contribute to the world. And when we reclaim it as medicine, we don’t just heal ourselves, we help heal the world.

Part 6: What I’ve Learned

Here are 6 lessons I’ve learned after leaving what I truly believed would be my forever career and doing a bunch of other, hard things:

Some people say “Starting is the hardest part.” In my experience that is a lie: every part is the hardest part. But that’s what makes it worth it, because…

Life truly is remarkable when it is an adventure requiring us to meet ourselves.

I will live in a box on the street before I will willingly return to working for someone who disrespects their employees and their community - not because I am not afraid of the street, but because I am more afraid of the future without change now.

None of us live in the same world, even if we live on the same planet and in the same community, and most people have no idea.

Most people do want good things for their neighbours and are super confused why things keep getting worse.

Working to prove something about myself fails, working in service of a dream too big to be realized in my lifetime creates deep fulfillment. All of us deserve the experience of reclaiming our work to build our dreams.

REFERENCES

Battilana, J., and Casciaro, T. ( 2021) Power for All: How it really works and why it’s everyone’s business. New York: Simon&Schuster Paperbacks

Drake RE, Wallach MA (2020). Employment is a critical mental health intervention. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 29, e178, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S2045796020000906

Insights from the State of the Global Workplace: 2025 Report https://www.gallup.com/learning/event/4907504/EventDetails.aspx

Lundqvist J, Lindberg MS, Brattmyr M, Havnen A, Hjemdal O and Solem S (2025) Associations between employment status, type of occupation, and mental health problems in a treatment seeking sample. Front. Psychol. 16:1536914. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1536914

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. Your insight on systems is so keen. It reminds me of debugging a complex AI model; sometimes you need to step far back from the local code to truly understand the emergent behaviour. Such a powerful reflection on values.