Does the World Find You Wanted or Wanting

How changing how I see myself in the world changed the world for me

If we want to have a resilient sustainable future, our worldview needs to shift to one where our work is seen as meaningful contribution to our community rather a way to exploit people to accumulate power and capital.

This shift is the only way to ensure we are all safe, because any exploitation accepted means all exploitation is acceptable.

How do we create healthier workplaces and healthier communities? Workplaces and communities are made up of people, and if we start to believe that we are worth it then we can do anything.

Understanding what it means to be wanted by the universe was transformative. I was no longer alone, no longer a burden, no longer something or someone to be resented but instead a cherished part of a living universe committed to a fully immersive experience of growth.

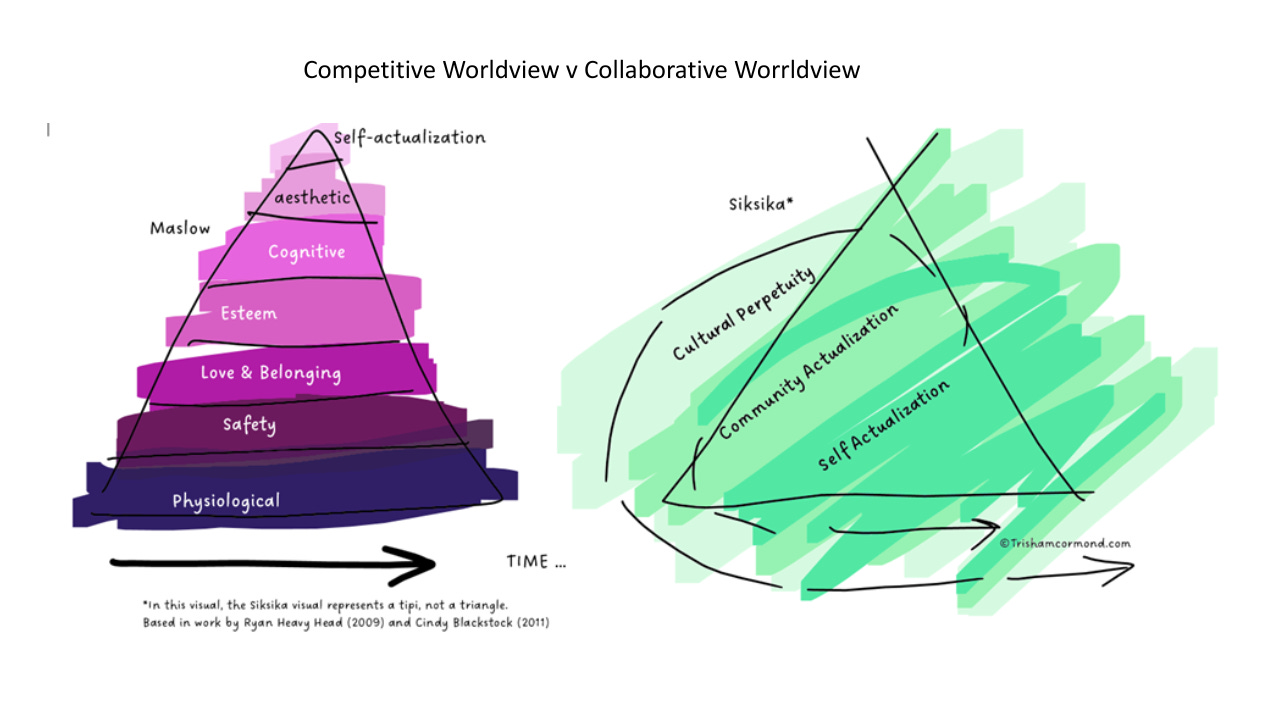

It started with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, spent some time with the Siksika worldview, and ended with me and the realisation that the argument misses the point.

Quick Maslow Refresher

(I usually need one)

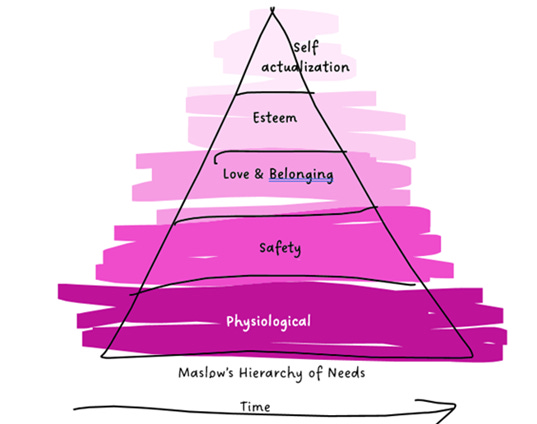

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a fundamental tool many professionals in multiple fields use as a base measure of the health of individuals, families, and communities and as what the individual is here to acquire.

First, satisfying physiological needs like food and shelter is the goal. Once these are satisfied, then individuals want to create safety. This includes health, financial security, and a stable environment.

The third need is finding love and belonging, being socially connected. These connection lead to the establishment of number four, Esteen, high regard by self and others, being recognised for your achievements.

Self-actualization, including creative pursuits, peak experiences, and moral development, was the fifth and final stop on this hierarchy for years.

This model is the basis for Maslow’s motivation hierarchy for people, seen in the top image. Those seven steps are seen as the driving force for an individual to continue to set goals.

However, in later years, Maslow added a final stage, self-transcendence, to both the needs and motivating pyramids, where we look to how we can be of service to others. This addition approaches the Indigenous understanding captured in the Siksika model.

Maslow’s model, the way we are taught, has little mention of family or community or obligations to each other and our world. The presentation of this as a hierarchy results in deeply competitive cultures and individuals focused on domination.

Indigenous Community Model Introduction (Don’t worry, there’ll be more later)

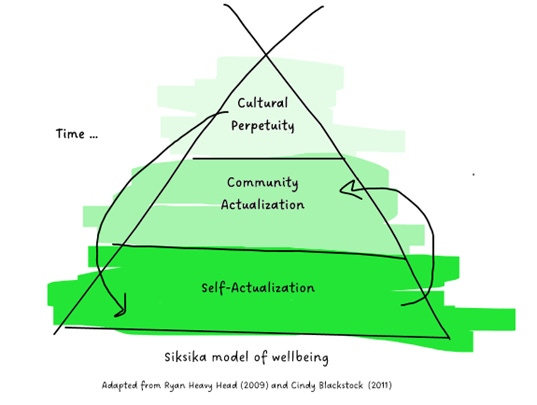

In Indigenous worldview, we live in community that supports us. I am Métis: We understand that our well-being is inextricably linked with the well-being of all our relations (wahkohtowin).

All our relations is not just ‘family’ but our neighbours, birds and animals, plants and insects, fish and all other creatures. It is the rocks and the air and the fire and the water.

This image is a tipi, not a triangle, to show it is our family and our community who provide for the basic needs of each other. This collaboration allows us to build stronger communities through mutual respect and care.

Tipis cannot be put up alone, just like one person alone cannot be safe or find love and belonging. Within our tipi’s. we have what we need to survive. Food, shelter, love and belonging, all of these are part of what it means to be community, and we provide them for each other working together.

Gabriel Dumont, one of our Leaders of the Hunt, says the first rule of the hunt is the first kill goes to the needy because it is an honour to be able to hunt.

The result of the Indigenous approach is accumulation doesn’t happen at the expense of our relations because it impacts sustainability: long-term cultural perpetuity. In this worldview, our motivation is stewarding our communities to create a healthy culture so our children and theirs can enjoy an abundant, stable future.

So … Who’s side is right?

There is an ongoing “who said”, “they said” debate about the intellectual, ontological, epistemic roots of these two worldviews. Often someone is framing it as Maslow’s “theft” or appropriation. That Maslow repackaged and exploited for personal gain wisdom shared with him by the Siksika, with whom he stayed for a few weeks in the early 20th century.

I have spent more time than I am comfortable with picking a side in this argument.

Eventually I realised this was another diversion: wisdom got swamped by arguments of provenance.

Rather than revelation there was annexation. A (in my opinion) bizarre interpretation of events and outcomes that keeps us arguing about who said it first rather than engaging about whether there’s value in considering how they may support each other.

I am not saying Maslow didn’t have elements of superiority of his own when he set out. I don’t know the guy, so I am also not saying he didn’t.

But there is a lot of deep-seated colonial hubris attached to believing Maslow somehow snuck onto Siksika land, hung around for a few weeks, and hoodwinked the Siksika into sharing this information with him that they otherwise would have written books about themselves.

That the Siksika were incapable of deducing Maslow was going to share this with his friends once he left.

Once I walked away from arguments of who this information belonged to, or who had the idea first, and started paying attention to what I could learn, my life changed slowly into miyo pimatisiwin, a good life.

What do I mean by that? After years of puzzling over how food and shelter were provided to babies, I finally understood that Maslow’s Hierarchy is incomplete because he had no reference to understand context: these ‘basic needs’ he identified all existed in a worldview of every being is wanted and interdependent on the others.

With this fundamental error, the cyclical and transcendent aspects of how community creates the individual were missed.

One might ask, “Why didn’t the Siksika explain this to him?” and the answer is the same from the opposite side: they had no world view in which every being was alone, without community. That is anathema to an Indigenous world view, not just on Turtle Island (North America). The Ubuntu also believe “I am because we are.”

“Owning’ information that, freely given, can make everyone’s lives better

[1]

The idea that this information is somehow owned and shouldn’t be shared freely is to believe the lie at the root of colonialism: that we are wanting. We prove our value through our utility. We are replaceable. This creates a perverse satisfaction in withholding knowledge.

To perpetuate this lie by arguing provenance is to completely miss the point of what the teachings are about.

The whole point of the Indigenous worldview, by whatever name you choose: Siksika teachings, Metis and nehiyaw miyo pimatisiwin, pan-Indigenous Seven Teachings, is that we are supposed to share them. This is how we create a good life, a healthy community, and a strong culture. Without freely sharing these ideas, how can we grow?

We can be part of an ever-shrinking pool of individuals focused on keeping the good stuff for themselves or instead join with those who want to be a part of an ever-expanding community of people who want to make life better for everyone.

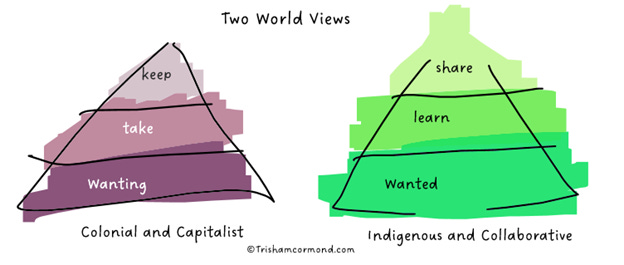

Colonial and Capitalist worldview

It always astonishes me that people want to make things harder on themselves because they don’t want to share their sweeties. People don’t understand that if you aren’t willing to share with your community, why would it want to share with you?

Eventually that resentment grows, no one is safe, and everyone is miserable counting their increasingly crappy hill of baubles. Nothing tastes as sweet anymore because the focus is defending the stuff or getting more stuff before someone else does.

More things is not the answer. It took me so long to understand that in a world that tells us our children are needy instead of needed, none of us ever feel comfortable or safe. How could we?

We are bombarded with messages that tell us:

We are wanting. Since we arrive here a burden, we must prove our worth and take what we need to do so.

Take what we need means we are constantly in competition, there is always someone ahead of us because they have more stuff.

Keep it for ourselves once we have it because there is no other way to assess whether we are winning. Others must have less so we can have worth.

Indigenous and Collaborative worldview

But there is another way to move through this world, one that feels like a balm to my soul after so long adrift. A perspective that locates us within beautiful webs of relationships that serves as my reason for hope.

When we know we are wanted by our community, we can learn and then share, building healthy workplaces and communities. We become curious because we are responsible for what happens in our life and accountable for our actions, we leave things better than we found them.

We know we are wanted because our communities ensure we have food and shelter and our parents are cared for.

We are not desperate to provide the bare necessities so we have time to explore the world, develop interests, learn what we can and share what we have learned.

We are wanted – our arrival here is a cause for celebration and joy, we arrive worthy and loved and protected as part of a community.

The first model restricts us to ever more hoarding because of the fear we will run out. The second model is a joyous expression of who we are here on earth, one where we are loved rather than a burden and so we are all in it together.

One of the biggest lessons I have had to accept is that if I want to get over whatever it is that holds me back, shame only works so much. The “get ahead or die trying” attitude makes me exhausted … what am I getting ahead of? Who am I trying to beat?

I would rather spend time with people who care about the same things I care about and work toward collaborative solutions that include everyone. This lights me up inside.

Mere survival is not our destiny.

Apparently Maslow stated he had never met a group of people so self-actualised as the Siksika. The Siksika, Blackfoot Confederacy, live on Treaty 7 territory in central Alberta and Maslow stayed with them in 1938 for several weeks.

I had a realization when I logged into work one morning: There are few things in this world that will drive people to do unthinkable things. Feeding themselves and their loved ones, satisfying basic survival needs is one of them.

food

water

shelter

belonging/safety

I know that when it comes to being hungry, I have gone to extraordinary lengths to feed myself because how else does one get anything else done if you can only think of food. I know I am not the only one.

In fact, I’d wager that many people go to work everyday because there is no community safety anymore. Most people don't seem to like their jobs, if prescriptions for anti-depressants and employee engagement scores mean anything, even if they appreciate the fact that their jobs let them buy food.

We are stuck trying to provide our basic needs, monopolised by wealthy people with more than they need, by buying crap we don’t need to make money for people we don’t like.

This is not to say people "don't want to work anymore" but rather that people want meaningful work that creates healthy communities rather that destroys them. We owe the generations after us a better legacy than the one we are currently leaving.

We want to feel safe enough to learn and then share what we have learned. Not actually live a nasty, brutish, and short life before some painful, to early death.

What does this have to do with the two worldviews and Maslow?

I am so glad you asked … we have spent so much time arguing about whether Maslow should get credit for the hierarchy of needs he published in the 1940s (over 80 years ago), that we have completely missed the opportunity to be curious about it.

An economy created by colonialism and extractive capitalism prioritizes private property to limit all access to these things that are freely available in nature. As community members, we feel increasingly unsafe because what used to be available is becoming less accessible.

Thus we no longer work because we want to, or because we are excited to be there and there is no culture workshop to fix that. The impacts of a competitive worldview on workplaces are:

* Increased mental health concerns and costs

* Decreased employee engagement, collaboration, and innovation

* Increased feelings of loneliness and frustration among staff

* Decreased information sharing and customer service

* Increased overhead costs and staff conflict

* Decreased trust in leadership and staff retention

By creating workplaces where people actually feel safe, rather than have to be there to meet their basic needs, we can unlock people’s ability to learn and willingness to take risks.

Final Thoughts

Maslow was writing about how people’s basic needs are met, they can ascend to great heights. It is a cultural perversion that in “The West” we believe we are supposed to be able to provide all of that for ourselves.

There is power and freedom in understanding that we flourish in community, with work that creates healthy sustainable futures that we all look forward too. If we feel unsafe, if we don’t have safety and food and a stable environment we cannot become fully realised People.

We can keep arguing about who thought of what (which does nothing to change our current reality), or doing research on why kids are hungry (the answer is because they have no food, it’s that simple). We could also try something different and accept that maybe both things are true. And then acting like it. Kids will always be hungry if they don’t have food.